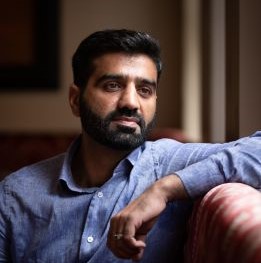

Naimat Zafary, from Afghanistan, is about to start at Sussex as a Chevening scholar. He describes his perilous departure from Kabul after the Taliban arrived in August and how he hopes his Sussex education can help his country.

“We have all cried for things we have lost – for first love, for financial losses – but the cry for losing your country is something you can never forget.”

Naimat Zafary’s voice cracks as he says these words. Since the Taliban swept into Kabul last month, his world has changed dramatically.

Naimat, a United Nations project co-ordinator, is one of nine Chevening scholars from Afghanistan due to start their studies at the University of Sussex this September. They have arrived safely in the UK and are currently in a quarantine hotel. But their departure was perilous and, at one point, seemed unlikely to happen.

Before the Afghan government fell on Saturday 14 August, the British Embassy in Kabul stated they were unable to process visas for the students in time to start their scholarships this year.

It was then that 35-year-old Naimat, who had applied three times before for the scholarship until successfully being accepted, became the spokesperson for their cause.

“I had been waiting years for this moment,” he says. “Education is the only thing Afghans need. So I spoke to the media and used Twitter and Facebook. My office warned me not to do it, but this is about rights and about education. You have to do it.”

When it became clear that the situation in Afghanistan was deteriorating, Naimat appealed to the UK Home Office for a permit to allow his wife and four young children, his parents, and his 16-year-old brother and 22-year-old sister to come with him.

“I couldn’t leave them behind,” he says. “My sister is single. I heard the Taliban were coming to houses and taking girls. It wasn’t safe for her. And my brother wants to follow in my footsteps, but there is no schooling now. How could I leave them?”

In the days following the Taliban taking control of Kabul, Naimat tried to convince his children that the gunfire in the street was a celebration and nothing to worry about.

“My three-year-old was asking if the Talib were coming to take her,” he says. “She is so young, yet she knew the name.”

On Sunday 22 August he received news that he and his family could travel to the UK. “I was so happy and grateful to the MPs and the people who had helped us.”

But the crowd of 15,000 people trying to leave via Kabul airport, and the difficulty of having small children and ageing parents, made their first attempt to get through the gate impossible.

“After 12 hours we came home and realised we needed a strategy,” he says. “We came back the next day, with all the Chevening scholars and a sign to show who we were. We held hands to make a circle, with the children and my parents inside it.

“We started the movement around 5pm and it took three hours to push. I thought at one point I shouldn’t have come. A mob of people came towards us. My nine-year-old daughter got kicked and was crying badly, so I put her on my shoulders for over an hour. My dad has a heart condition and diabetes and was not in a good position. But you cannot go back, you cannot go forward.

“People were shouting, ‘don’t come.’ The day before, ten people were crushed to death. Finally, we crossed and then, because we had the Chevening sign with us, a UK soldier saw it and said he’d been waiting for us.

We had been standing in a pool of the dirtiest water – you could smell it on you for two days after. We gave our hands to the soldier and he said, ‘I am here to help you out.’”

By first light the next day, Naimat and his family and fellow Chevening scholars were on a plane, first to Dubai, and then to London Heathrow. Two days later, a bomb attack killed more than 90 people at Kabul airport. The thought that it could have been him and his family chills Naimat.

“It was just a matter of hours since we were at the same place. Some families we saw had spent three or four nights there. It’s very difficult to forget them. You think that if you had stayed there one or two nights you might have been the victims.”

This is not the first time Naimat and his family have fled their homeland. In 1991, when he was seven, his parents took him and his six siblings to Pakistan to escape civil war. They sold their home and land and didn’t return until 2002.

“It was different for me then because I didn’t understand what it meant for a government to collapse,” he says. “Now for me it’s very hard, because you have more things on your mind, more dreams and wishes. But the reality is that we have been living in a war for 40 years.”

Naimat realised early on that education might help him and others out of poverty. From the age of 10 he worked for nine hours a day weaving carpets and selling boiled eggs to pay for his three hours a day of schooling in Pakistan.

“Because I’ve been working for a long time, it makes you ready for the world and the things that come to you,” he says. “It also makes you ready for leadership, because you know what’s going on in the street.

“I know that you only have power if you have education. I am proud because I am in one of the most prestigious education systems and I’m working for the UN.”

Naimat, who was an undergraduate and a masters student at Kabul University, has worked for the National Environmental Protection Agency and the Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development in Afghanistan.

He began working for the United Nations Development Programme in 2013, focusing on human development, and in 2020 published a report, Pitfalls and Promise, about the potential of Afghanistan’s extractive industries.

He wanted to study for an MA in governance, development and public policy, based at the Institute of Development Studies at Sussex, because of its global reputation for excellence and because two of his friends had also studied at here.

“I have seen their knowledge and their understanding inspired me,” he says. “And in terms of development studies, the course I have chosen is top notch.

“Some of our provinces are 85 per cent to 90 per cent multi-dimensionally poor, so the only option is engaging society and planning. I want to bring about positive changes by involving communities, not blindly implementing policies without seeing what’s happening on the ground.”

Now, with the future uncertain, he can only speculate. “We always have to be hopeful. The nation will rise up again. And I will be studying the course and trying my best to understand it.

“I hope I will be in a position to help my country. If I cannot go back, then an idea is that I will be able to give lectures to my university virtually and transferring my knowledge to a new generation there.”

While he has escaped the danger, he is still haunted by his experience. “It’s been three weeks and I cannot sleep properly – I think I am in the queues, in the street. The whole scenario keeps coming to your mind and your dreams.”

He still has two brothers and a married sister in Afghanistan – who was hoping to finish a degree in medicine this year – and he fears for their safety. He is angry that Afghanistan’s President Ashraf Ghani left the country without warning his people or giving them any chance to prepare.

But Naimat is looking forward to making the UK and Brighton his home for the time being and says he feels so honoured to be a student at Sussex.

“People have been so welcoming,” he says. “I was in the park with my family and some women asked me where I was from. They said we’re so sorry for what’s happening in your country. They welcomed me so nicely. They don’t know me but they gave me the feeling of being friends, of being in a family. When people say ‘welcome to your new home’, it touches your heart.”

In keeping with our status as a University of Sanctuary, today we have launched a fundraising appeal to provide vital support for our Afghan students, like Naimat. Please click here to give whatever you can afford to support these students as they try to rebuild their lives.