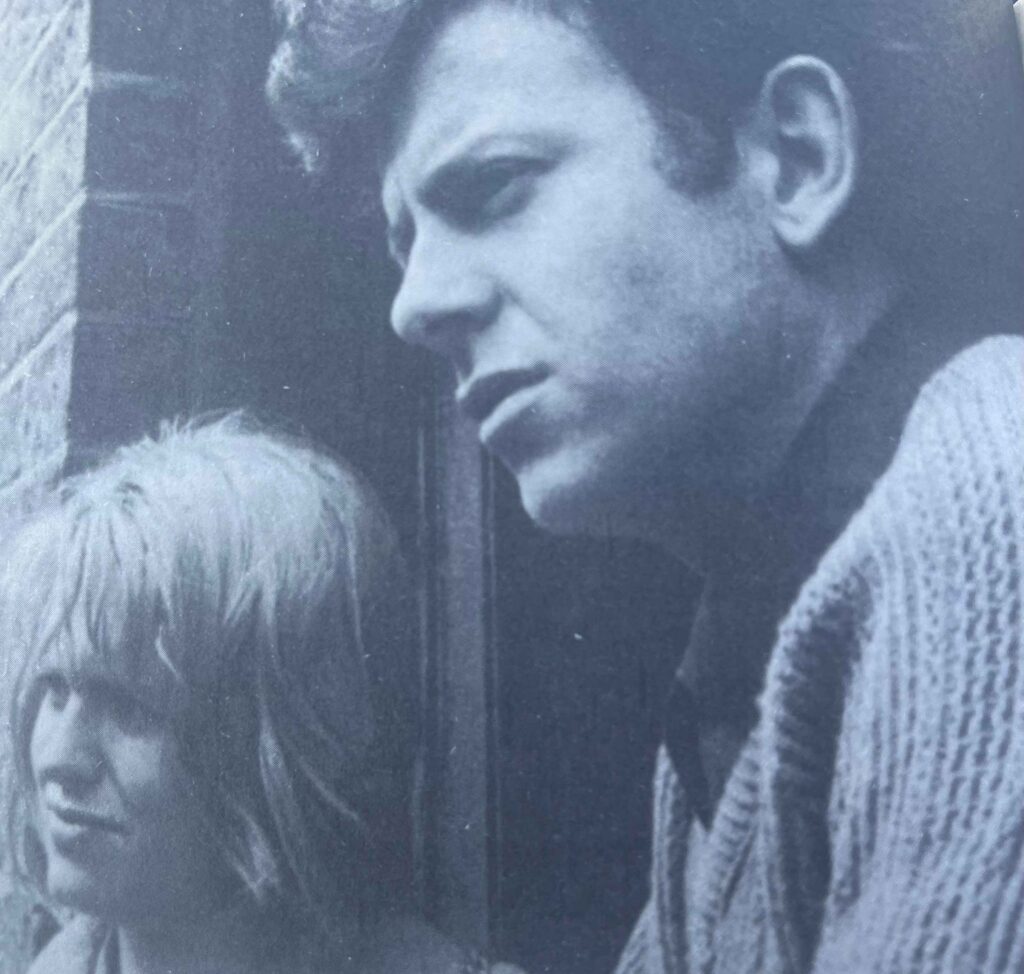

Ray Brooks, actor and Brighton boy, who died this week, starred with Carol White in Cathy Come Home in 1966.

“The most important piece of dramatised documentary ever screened,” according to The Sunday Times, it shone the light on the plight of homeless families and children living in squalor in temporary accommodation.

It gave a huge boost to the fortunes of the recently founded housing charity Shelter and led to the creation of a network of community-based housing associations across England.

Among them was Brighton Housing Trust (BHT), now BHT Sussex, set up in 1968 with one house in Islingword Road, Hanover, and still fighting the good fight.

The Ken Loach film was also the making of Ray Brooks, whose mum was a Brighton and Hove Buses clippie.

At about the same time he starred in the award-winning The Knack … and how to get it and a long and successful career in film and TV followed.

Cathy Come Home is definitely worth another look today. It gives the lie to those, usually on the Right, who seek a return to an illusionary England of wine and roses and those who believe everybody, especially young people, had it easy 60 years ago.

They didn’t then. They don’t now. We are in the middle of a national housing crisis exacerbated by 14 years of chronic under-investment under Tories and Lib Dems (don’t forget the coalition).

Some 130,000 families and 170,000 children spent last night in temporary accommodation in England.

Brighton and Hove has its own housing crisis, with 3,580 homeless families and 1,000 children in temporary accommodation, according to figures published earlier this year by Shelter

The depth of the local crisis is reflected in the BHT response. Last year it supported 10,683 clients and prevented 2,142 cases of homelessness.

The visible signs of Brighton and Hove’s crisis can be seen in the walking wounded – the city’s street homeless men and women.

The hidden signs are sofa surfing and the rising number of young people who have no choice but to continue to live at home.

Steepling rents and mortgages are beyond the means of many sons and daughters of the city.

The good news is the Labour government is promising to build 1.5 million new homes but so far there is no meat on its social housing bone.

Meanwhile, private landlords, including those providing sub-standard homes and “temporary” accommodation, are trousering a large wedge of the £23 billion – and rising – doled out in housing benefit in England each year.

This colossal figure, by the way, is bigger than the annual individual budgets all government departments, apart from health, education and defence.

Not a penny of it is spent on building new homes.

“We get run down because we ain’t got houses,” says Ray Brook’s character Reg in Cathy Come Home. “It’s no good, this life we’ve been leading. I wonder sometimes when it’ll end.”

Labour has promised to end it. By picking up the housing challenge and keeping its promise, difficult although it might seem, it could make a fundamental difference to so many impoverished lives like those of Cathy and Reg.

To BHT’s great credit, almost one in five of its staff first made contact with the organisation as a client – proof, if proof were needed, that a decent home can make all the difference.

Bill Randall was the first Green leader of Brighton and Hove City Council, the first Green mayor of Brighton and Hove and a former trustee of BHT.