Brighton and Hove’s young people are showing greater levels of anxiety, according to youth worker Ben Glazebrook.

Mr Glazebrook, who manages the Young People’s Centre, in Ship Street, Brighton, and represents the Brighton and Hove Youth Collective, said that this reflected more families where there was anxiety.

He didn’t suggest the problem was peculiar to Brighton and Hove. And a mental health commissioner praised work to help children in this area in three secondary schools and eight primaries in Brighton and Hove.

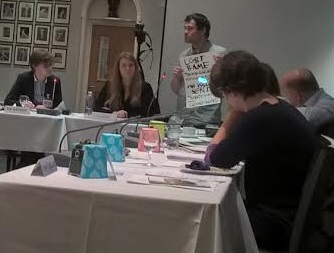

Mr Glazebrook was explaining the need to support third sector youth services in Brighton and Hove as he gave evidence to the Fairness Commission set up by Labour-led Brighton and Hove City Council.

He spoke about the need for cultural change although he added: “I don’t want to moan about the council.”

He said: “We need to be creative, responsible and flexible. Is the council creative, responsible and flexible?”

“The culture of the council tends to be risk-averse, cautious and compliant. There are signs that it is changing including this week at the early help intervention conference?”

He gave an example, typified by the response, “We don’t do that.” He said: “We need to move to a culture of, ‘How can we do that?’”

He also said: “How do we create a more permissive environment?” It may not always be desirable, he said, but sometimes it was.

Mr Glazebrook said: “A lot of the youth work we do is based on relationships. It’s about being where young people are. I think it works fairly well generally.”

He said that some of the young people that he and his colleagues were working with in places such as Whitehawk and Hangleton and Knoll were from fairly deprived areas.

He said: “You need to develop trust. Some of them have been let down a lot in their lives so trust is vitally important.

“A lot of our work is youth-led. The whole programmes are designed with the young people coming in. It’s not just a group of adults telling young people what to do.”

He said that it wasn’t all bad news. He also urged the council to take a longer-term approach, putting funds into locally managed community based services for five years.

It made sense, he said, to build on the assets of communities – like the Youth Collective which is embedded in communities.

In hard financial times, he said that third sector youth services employed few staff but worked with lots of volunteers.

He pointed out that the council gave the Brighton and Hove Youth Collective a £400,000 grant but received the equivalent benefit of £1 million.

One young member of the audience – from Right Here – pointed out how few young people were contributing to the work of the Fairness Commission.

Right Here Brighton and Hove is a project led by young people aged 16 to 25 years old to promote the mental and emotional wellbeing of young people.

Vic Rayner, who chaired the meeting, pointed out that the Youth Mayor was a member of the Fairness Commission.

Clair Barnard, from the Early Childhood Project, urged the council to listen to parents and families.

She said consultation tended to be driven by council priorities, Ofsted priorities and NHS priorities – but not the priorities of those using services.

She gave an example of a seemingly pointless consultation where families were asked: “Do you want a room renamed Raspberry or Strawberry?”

Her colleague Alex Peterson, who chairs the Independent Network for Early Years Services in the Voluntary Sector, said that it was a real consultation. The two fruit choices were dictated by the colour of the room as it had just been repainted.

And Clair Barnard said: “In Brighton and Hove we have more pilots than Gatwick. Families have been consulted a lot but it’s made no difference.”

In her summing up, Vic Rayner mentioned communication as one of themes to have emerged.