The number of new homes being built each year continues to decrease yet the construction industry finds itself needing more staff than ever.

The cost of building continues to rise yet construction firms are making less than ever before and the number going bust is also rising.

And if that’s not troubling or confusing enough, the suicide rate for construction workers is four times the national average for other sectors.

I’m disappointed by the latest new on the industry but I can’t say I’m surprised. Before I was a developer, I used to run a construction business. I didn’t hate every minute of it but it was pretty close.

The whole industry is in a malaise. Years of under-investment in training, layers of pointless bureaucracy and yet a complete void of singular leadership, a wild-west approach to settling arguments, a total reticence to take on new technology, a boom and bust culture.

And if that wasn’t enough, most major firms make a pittance of a profit margin. Sure, there are worse industries, but not many.

Construction, according to the government, “underpins our economy and society.” And its largest single sector is new-build housing – estimated to be worth around £60 billion a year over the next decade.

That figure however, is based on the continued target of 300,000 new homes a year – a target that has never been met and isn’t going to be.

The number peaked in 2019 and continues to get lower every year, with the latest planning reforms likely to see new-builds in the next few years under 150,000 a year.

According to the Centre for Cities think-tank, the country is already missing some 4.3 million homes to cater for its population, which is increasing by 600,000 plus every year or more. If you have more people, you need more places for them to live.

My point therefore is that this is a sector that the country relies on. It has a product that is in huge demand through years of chronic under-delivery – and there is clearly huge demand.

The industry will continue to grow and there is vast scope for technology to be employed to help it do so. And yet … the industry is in a clear decline.

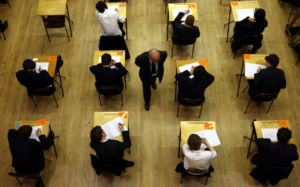

Let’s start with the staffing shortage. Back in the late 1990s, the New Labour government had a dream of sending everyone to university.

An admirable desire to see everyone have equal access to higher education is certainly nothing to be sniffed at, but not everyone wants or needs a degree in ancient history or media studies.

Some people actually like to be outside or making and doing things and that shouldn’t be seen as a less worthwhile career. This is by no means a single party issue either.

Since 2010, no part of the education system has suffered harsher cuts than vocational training but this is the sector with more students from the most disadvantaged backgrounds.

Funding per pupil has been reduced by 12 per cent. Worse still, 40 per cent of apprentices fail to complete their courses.

Not only are we not training enough people but, and I hate to say the word, since Brexit we’ve had a lot of qualified and experienced construction workers leave. Somehow, we need to fill that gap and we haven’t either in the short or long term as yet.

Then there is the leadership, or lack of it. In researching this article, I found the Construction Leadership Council website. Well, I’ve worked in and around this industry for 20 years and it’s the first time I’d heard of them.

I asked around and no one else had heard of them either yet they are out there co-signing government letters. Their website has a lot of aims but not much else.

Part of the problem here is that, as a contractor, there are a lot of bodies competing to tell you what to do.

If you undertake a new-build, you have to register not only with the council’s building control team but you’ll need a new home warranty too.

That’s the NHBC (National House Building Council) for the big contractors and other alternatives for everyone else – and don’t get me started on how dreadful the NHBC are.

Then you have to pay a levy to the CITB (Construction Industry Training Board), supposedly for training.

The products you use must comply with HSE (Health and Safety Executive) rules, BBA (British Board of Agrément) and BS (British Standards) standards accreditation. You’ll need to satisfy all the planning authority conditions and so on.

And if you’re confused, there is apparently a “single voice for construction professionals” called the CIC (Construction Industry Council).

If they’re busy, though, there are some other bodies also claiming to be that same single voice, plus every subcontractor trade has its own bodies offering help and demanding fees.

What is truly amazing though is that to be a main contractor, building homes and organising work in a dangerous industry, you don’t have to be qualified in anything, nor registered, nor frankly even competent.

Might that not be a good start? Sorry to stop the gravy train for all these organisations. But wouldn’t it make more sense for there to actually be a single place contractors needed to register so that they could get the right information and training?

I’m generally not in favour of oversized, over-bearing authorities. But the current system really isn’t working so maybe we should give it a go, as long as we can ignore all the others at the same time.

The disputes system also needs an overhaul. I’ll spare you that issue for another day. But suffice to say the incompetence of it is the main reason I leave construction to others now. You might as well flip a coin rather than waste money on lawyers in the current system.

Then technology. Think about how cars are made – the laser-guided robots assembling vehicles in the spotless factories. Now think about the last building site you walked past. Spot any comparisons? Me neither.

Factory-built homes were supposed to be the next big thing for about two decades on the go. Yet only earlier this month, Legal and General shut its Leeds factory after having lost £180 million in seven years, with many other modular homes businesses having gone the same way.

There are a multitude of upshots from all of this failure but a fairly simple one is cost. Construction firms go bust when costs rise because a lot of them work on relatively fixed-price contracts.

As materials and labour prices increase, profit margins get squeezed to zero. There have been huge material price increases over the past two years, just like in every industry. But labour rates are increasing too, with many trades in high demand and charging incredible day rates.

If you know a roofer or a bricky and they’re claiming poverty then they must be one of the ones that goes home at 2pm every day. Which is a lot of them.

As building costs then rise, what we can actually build reduces. As an urban developer, any area where resale rates are less than £400 per square foot is likely to be impossible to build in now. We couldn’t even break even – and that assumes zero affordable housing.

The government has a hell of a job on its hands. The industry needs not just reinvention but revolution. Let’s hope all the talk of building new homes being the cornerstone of debate at the next election doesn’t just end there.

Ed Deedman is a director of Cayuga Homes.

The reason is the planning system. SMEs train 7 in 10 construction apprentices, make up 90% of training capacity, typically employ within 20 miles of their head office and build 9% of homes.

They can’t secure pipelines or planning certainty because the system is so broken and risk based.

It therefore doesnt take a genius to work out that if you want more skilled workers and more homes, you need to enable, not hinder SMEs. Planning uncertainty is even killing offsite developers, as they need certainty for their factory like strategy.

It’s tiring saying this over and over and over and over, for eight years but the narrative still being about evil, profiteering developers, or Persimmon Syndrome, not the reality of the housebuilding industry.

Couldn’t agree more.

Regarding staffing, it would make sense to push training opportunities such as apprenticeships. Even if they ultimately decide to move on from a company, the overall good it will do for the industry as a whole seems indefeasible, to me.

We certainly need more apprenticeships and we actually have, as country, an enormous amount of money sitting there to do it. In the last 5 years, £4.3Bn has been raised by the apprenticeship levy on larger businesses and remains unspent. Thats just bad administration.

It’s an unfortunate reality that apprenticeships in this country are often poor value for the apprentice. Questionable educational merit, menial duties, no interest in progressing the apprentice further, below-minimum wages, and a serious lack of retention. Indeed, a number of employers are becoming notorious as apprenticeship mills, dropping fully trained apprentices as soon as possible to go back to square one. This is all a wages dodge, exacerbated by apprenticeship levy rules and substandard oversight. Training providers (the colleges, etc. providing trainers to businesses) are incentivised to be complicit and push candidates through, as they must bid for business.

It’s a crying shame, as the idea of apprenticeships would fill a great need in society, but greed conquers all.

Yep, that’s true a lot of the time too. As above, the Government has the money, it just appears to have no clue as to how to spend it properly so apprentices get the courses and training they, and the country, needs.

How would you recommend the council utilise apprenticeships more effectively?