Watching the scenes at Kabul airport this week left me and many others with feelings of overwhelming grief and anger – grief for the millions of Afghan women and girls in particular who were promised a brighter future and the opportunity to learn, work and pursue their dreams and anger that the many pledges made to the Afghan people over the past 20 years have been broken as they were abandoned to their fate.

The stories being told by terrified Afghans are heart-rending. There are the women students who are now hiding their diplomas and certificates for fear of punishment and in the belief that, in any case, their qualifications will be useless as they will not be allowed to use them.

There is the female mayor who says that she is now waiting for the Taliban to come for people like her and kill them.

There is the Afghan journalist, now in hiding with his family, who said: “There was a lot of promise, a lot of assurance, a lot of talk about values, a lot of talk about progress, about rights, about women’s rights, about freedom, about democracy. That all turned out to be hollow.”

That journalist is in danger of being proved right.

We have to do whatever we can now to honour our commitments to the people of Afghanistan. That starts with fixing our failed refugee and asylum-seeking system.

For all the hand wringing of government ministers in the last few days, the reality is that their actions over the past few months have left thousands of ordinary Afghans in terrible danger.

Interpreters and contractors who worked side by side with UK forces have been refused resettlement on the grounds that they were technically subcontractors. That is shameful.

I fear for the thousands of ordinary Afghans who supported the UK in delivering aid and supporting other projects, often in the interests of our foreign policy objectives. They are now at real risk of being seen as collaborators working against the Taliban’s interest.

The NGOs they worked with are now powerless to help them but the UK government are not, yet we have heard very little about what the government are doing to persuade and support them.

Many are not covered by the Afghan relocation and assistance programme because they worked for UK organisations other than the government – for NGOs (non-governmental organisations) and other civil society organisations, even though they were paid by UK aid.

They are in extreme danger, so that ARAP (Afghans Relocations and Assistance Policy) programme must be expanded to encompass them, too.

The scheme was far too late to get off the ground and only started in April when Taliban advances and atrocities were already all too apparent, and it has been drawn all too narrowly.

It must be amended to allow visas for the family of people who would have been eligible but who have died and for people who have fled Afghanistan but would have been eligible had they remained in country.

The resettlement scheme announced by the government last night (Tuesday 17 August) is welcome but it is not enough.

Places must be based on need, not on numbers. There should be no artificial cap. When the government are already failing to achieve their existing target of settling 5,000 refugees a year, we need to hear an awful lot more about how ministers are planning to deliver for Afghan refugees and guarantees that local government will be properly funded to work with them.

I call on the Home Secretary today to abandon the resettlement-only plans set out in the Nationality and Borders Bill, which would criminalise, or deny full refugee status to, those who make their own journeys to seek asylum in the UK.

I call on her to grant immediate asylum to Afghans already waiting for status in the UK, release all Afghan nationals from detention and urgently expand the family reunion route so that Afghans can be joined by other members of their family, including siblings and their parents.

I was contacted by a constituent who used to work for the EU delegation in Kabul and whose siblings all worked for allied forces.

He has asylum here in the UK and his siblings have asylum elsewhere but his mother is left alone, desperate and very much a target. We absolutely need to widen the family reunion rules.

We also need not just to properly restore aid but to increase it. The Foreign Secretary said that it is being doubled. I welcome that. But it is still less than the 2019 figure. We need to recognise that the need today is so much greater than it was even in 2019.

There are many lessons to be learned from this disaster. It looks as if our intelligence might well have been inadequate, our promises to the Afghan people worthless and our duty of care to ordinary Afghans who worked with us patchy and unreliable.

More than that, this Afghan tragedy should be the catalyst that finally forces us to rethink how the so-called war on terror is fought.

The debacle in Afghanistan, with the loss of almost a quarter of a million lives, is just one of four failed conflicts in the past 20 years.

Western military action in Libya and Iraq and the air war against ISIS in Syria have all failed to achieve their objectives.

ISIS is still active in Iraq and Syria, ISIS and al-Qaeda are active across the Sahel and eastern Africa, and there are still links with Afghanistan.

We urgently need to learn the lessons of failed wars of intervention and take an honest look at the objectives behind our foreign policy.

For too long, protecting British interests has been about stability and safety through access to oil, maintaining the current balance of power and a very inconsistent approach – to put it mildly – to human rights and democracy.

When we ally ourselves with countries such as Saudi Arabia, our moral credibility to speak about human rights is fundamentally undermined.

We need a longer-term approach, including stopping arms sales to oppressive regimes that do not abide by international law, and a more consistent approach to democracy across the world.

The government like to boast of our country being global Britain. If that is to mean anything, it surely has to be an opportunity to finally develop the ethical foreign policy that we have spoken about for so long, focused on seeking to build international consensus with co-operation, security and human rights at its heart.

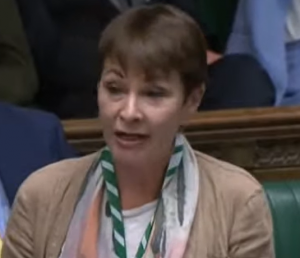

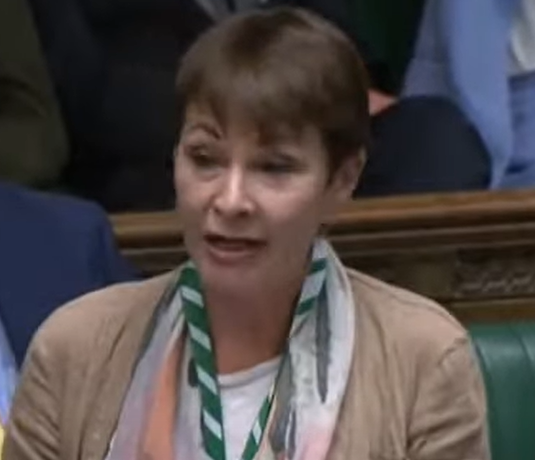

Caroline Lucas is the Green MP for Brighton Pavilion. This is the text of a speech that she made in the House of Commons on Wednesday 18 August.

The UK is a very expensive place to resettle refugees and as a country we are broke. Perhaps instead of campaigning for unlimited numbers of Afghans to move to the UK, to a country where they have no cultural connections, we should be diverting our foreign aid budget to places in Africa or countries such as Turkey who for money would agree to house them and help them set up businesses that we in the West could support to help give them viable incomes and a reasonable future. This way we would be able to help a lot more without putting additional pressure on housing and taxpayers many of whom are skint after the pandemic here. One year’s rent in Brighton would buy them a freehold house in Turkey.